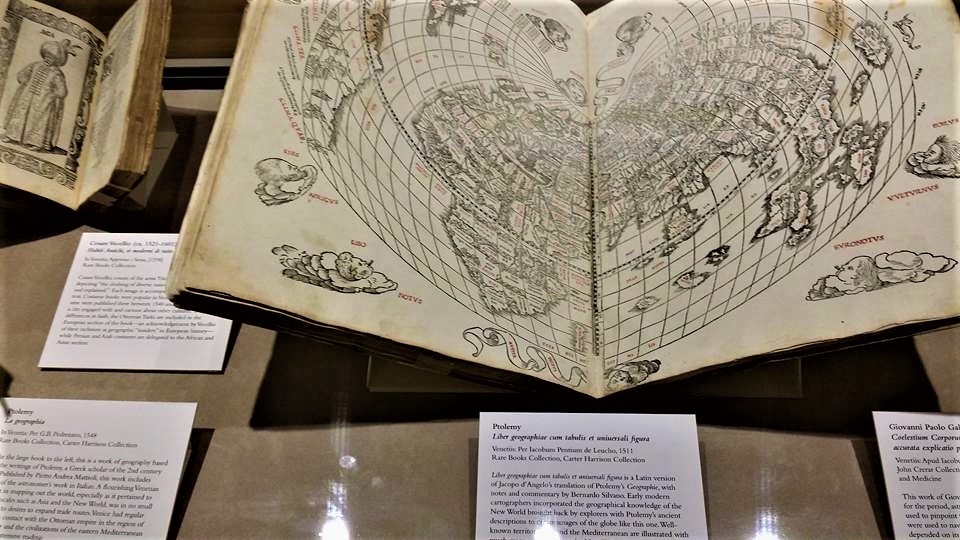

In Spring 2017, the university’s Special Collections Research Center exhibit space hosted an exhibit on “Tensions in Renaissance Cities” curated by a team of University of Chicago graduate students and other program associates. Led by Ada Palmer (History faculty) and graduate student co-curators Hillary Barker and Margo Weitzman (Art History), the eighteen-member exhibit team explored major Renaissance capitals from Constantinople to Mexico City, and the tensions which characterized them, ranging from religious and confessional conflict, to city rivalries, to gender norms.

In Spring 2017, the university’s Special Collections Research Center exhibit space hosted an exhibit on “Tensions in Renaissance Cities” curated by a team of University of Chicago graduate students and other program associates. Led by Ada Palmer (History faculty) and graduate student co-curators Hillary Barker and Margo Weitzman (Art History), the eighteen-member exhibit team explored major Renaissance capitals from Constantinople to Mexico City, and the tensions which characterized them, ranging from religious and confessional conflict, to city rivalries, to gender norms.

Together, the team published a print catalog of the exhibit, and hosted a visiting reception for attendees at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the Renaissance Society of America, which took place here in Chicago. Participants included Rose Malloy and Michael Hosler-Lancaster (History) who whose case examined Venice’s view of Constantinople/Istanbul, John-Paul Heil (History) who examined humanist magic in Florence, Tali Winkler (History) who examined Jewish humanist, Nora Lambert (Art History) who looked at the transformation of Constantinople to an Islamic city, Eufemia Baldassare (Romance Languages) who looked at patronage and power in Florence and Rome, Cosette Bruhns (Romance Languages) who examined Petrarch’s impact on Florence’s urban space, Elizabeth Tavella (Romance Languages) who examined male efforts to define the lives of urban woman, Aimee González (Musicology) who examined editions of the Psalms from Catholic Paris and Calvinist Geneva, Nicholas Bellinson (Committee on Social Thought) and Caryn O’Connell (English) who looked at London’s relationship with its countryside and its identity as an intellectual center, Lucia Deliani (Northwestern Rhetoric Program) who examined confraternities in Renaissance republics, Stuart McManus (SIFK Postdoctoral Researcher) who examined Mexico City’s relationships with Roman and Mesoamerican antiquities, while co-curator Hilary Barker examined Roman Ruins, Margo Weitzman examined Florentine humanism, and Undergraduate Research Fellow Julia Tomasson (History and Philosophy of Science) edited the print catalog.

Exhibit Introduction: Great and Wretched Cities

Lavish courts and towering cathedrals, entrancing polyphony and artistic masterpieces—our romantic fascination with the cultural glories of the Renaissance often eclipses one truth, recorded by astute observers of the age like Machiavelli, that the era of Michelangelo and Shakespeare was, in many ways, darker than the “Dark Ages” which it named. The crisis had one unexpected cause: progress. In the centuries after the Black Death, regenerating urban centers, strengthened by financial and commercial innovations, linked together to form an increasingly interconnected society. Soon English wool was no longer finished at home, but exported to be woven and dyed in Italy, before shipping out across trade networks which stretched from the Middle East deep into the New World. As Europe’s economic bloodstream strengthened, the same increase in trade and travel which let architects build with exotic stones and scholars recover lost Greek manuscripts also transmitted diseases with unprecedented speed and ferocity, while larger, denser cities were richer breeding grounds for violence and contagions. As wealth and power flowed in, richer states could muster larger armies, innovative weaponry could shed blood on unprecedented scales, and ambitious rising families could hire mercenary forces larger than frail governments could withstand.

Lavish courts and towering cathedrals, entrancing polyphony and artistic masterpieces—our romantic fascination with the cultural glories of the Renaissance often eclipses one truth, recorded by astute observers of the age like Machiavelli, that the era of Michelangelo and Shakespeare was, in many ways, darker than the “Dark Ages” which it named. The crisis had one unexpected cause: progress. In the centuries after the Black Death, regenerating urban centers, strengthened by financial and commercial innovations, linked together to form an increasingly interconnected society. Soon English wool was no longer finished at home, but exported to be woven and dyed in Italy, before shipping out across trade networks which stretched from the Middle East deep into the New World. As Europe’s economic bloodstream strengthened, the same increase in trade and travel which let architects build with exotic stones and scholars recover lost Greek manuscripts also transmitted diseases with unprecedented speed and ferocity, while larger, denser cities were richer breeding grounds for violence and contagions. As wealth and power flowed in, richer states could muster larger armies, innovative weaponry could shed blood on unprecedented scales, and ambitious rising families could hire mercenary forces larger than frail governments could withstand.

This exhibit lays out a geography of tensions which characterized Renaissance cities. In a world still plagued by war and banditry, urban growth often meant density rather than sprawl, as swelling populations jockeyed for space within the circumferences of city walls. Crowded and wealthy cities became powder kegs, where old tensions—between men and women, citizens and visitors, Jews and Christians, religious and secular authorities—channeled the energies of new and increasing factional and economic rivalries. Shakespeare’s Montagues and Capulets are fictitious portraits of a real phenomenon, and such violence often brought ruin on far more than just two houses. Great families led patronage networks which included hundreds of clients from many social classes, whose members lived only a few blocks from their bitterest rivals, and whose alliances reached out into dozens of neighboring towns and distant capitals. Tensions between cities intensified as well, as economic interdependence, and printing which enabled the faster circulation of news and new ideas, allowed tumults in one city to bring strife to another half a world away. Cities competed to frame their political identities, claiming uniqueness and dignity by presenting themselves as the capitals of particular trades, religious movements, cultural innovations, or political structures, often in ways which contradicted or challenged the identities claimed by their neighbors. Art, literature, and culture recorded these tensions and also relieved them, offering bloodless avenues for competition, and a release valve for the pressure that kept Renaissance cities forever on the edge of violence.

Exhibit Highlights:

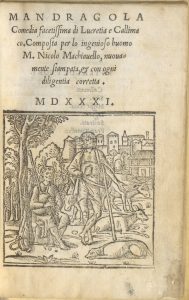

Vinegia: Per Nicolo d’Aristotele detto Zoppino, 1531

Machiavelli survived many Florentine tumults: the death of Lorenzo de Medici, the French Invasion, the expulsion of the Medici, and the rise and fall of Savonarola. He worked tirelessly for the republican government that ruled Florence after Savonarola’s execution, but was banished after the Medici recaptured the city. Machiavelli wrote this satirical comedy The Mandrake during his exile, and packed it with criticisms of religion, politics, and society, depicting lustful conspirators, a corrupt and greedy friar, and a mother who urges her married daughter to commit adultery. The play’s shocking ending, in which adultery works out well for all involved, starkly reverses the moralizing lessons which usually shaped Renaissance drama.

MS384 Book of Hours, France ca. 1500

Books of Hours were extremely popular devotional manuals throughout Europe, and especially France where skilled illuminators produced them for private devotion. At their core, they contain a sequence of prayers to the Virgin Mary recited throughout the day. Reformation leaders like Jean Calvin (1509–64) opposed both this focus on devotion to Mary and the inclusion of sensual images. This illumination at the beginning of the Penitential Psalms depicts Bathsheba bathing under King David’s gaze. David is believed to have written the Penitential Psalms as an act of repentance for his transgressions, including his adultery with Bathsheba, the wife of one of his soldiers.

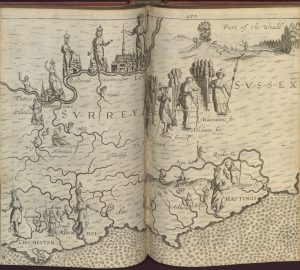

Poly-Olbion, or A Chorographicall Description of Tracts, Riuers, Mountaines, Forests…

Michael Drayton (1563-1631)

London: Printed by H. L. for Mathew Lownes, 1613.

Michael Drayton (1563-1631) wrote epic, pastoral, satirical, and historical poetry, plays in verse, also religious poetry, some of which was banned and destroyed by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Drayton was a court favorite of Queen Elizabeth, but rejected by her successor James I. In 1610 he published the first section of his massive 15,000 line Poly-Olbion, whose verses survey the topography, history, natural history, and legends of Britain’s many counties. While Drayton invoked a Muse to inform his work (“Thou Genius of the place”), he published his poem with annotations by a scholar who cast doubt on the suitability of genii loci to scholarly enterprises. As an artifact, Poly-Olbion embodies early seventeenth-century England’s tensions concerning the proper sources of knowledge. It also captures tensions about the sites it describes, departing from contemporary pastoral conventions by praising, not just the spirit of rural locales, but also the genius of cities, above all “Great London.” Drayton celebrated London as a great source of wealth to England, though he deplored the squandering of this wealth by idle gentry,

Michael Drayton (1563-1631) wrote epic, pastoral, satirical, and historical poetry, plays in verse, also religious poetry, some of which was banned and destroyed by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Drayton was a court favorite of Queen Elizabeth, but rejected by her successor James I. In 1610 he published the first section of his massive 15,000 line Poly-Olbion, whose verses survey the topography, history, natural history, and legends of Britain’s many counties. While Drayton invoked a Muse to inform his work (“Thou Genius of the place”), he published his poem with annotations by a scholar who cast doubt on the suitability of genii loci to scholarly enterprises. As an artifact, Poly-Olbion embodies early seventeenth-century England’s tensions concerning the proper sources of knowledge. It also captures tensions about the sites it describes, departing from contemporary pastoral conventions by praising, not just the spirit of rural locales, but also the genius of cities, above all “Great London.” Drayton celebrated London as a great source of wealth to England, though he deplored the squandering of this wealth by idle gentry,

…whose disproportion drawes

The publique wealth so drie, and only is the cause

Our gold goes out so fast, for foolish foraine things,

Which upstart Gentry still into our Country brings.

Drayton condemned England’s dependence on foreign luxuries popular with the gentry, like silk and tobacco (“trash… of which we nere had need”), to the neglect of domestic products (“our Tinne, our Leather, Corne, and Wooll”). This polemical digression synthesizes tensions between urban and rural, public and private, foreign and domestic.

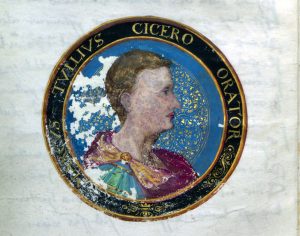

Antiquity offered an alternate nobility, deriving, not from blood or chivalry, but from the memory of Rome. Art intimidated, cowed, and tempted, and visitors to Italy quickly realized they too could use classicism to glorify themselves. For glory-hungry cities and monarchs alike, cultural competition had long been an alternative to conquest. Patrons of the classics could outshine rivals by possessing the most learned Greek scholar, the most classical palace, or the most extensive library. Soon every city in the European sphere hungered for Roman sculptures, Italian artists, and humanist scholars. For factions within cities, displaying power through a festival song, a statue, or a learned sermon was a bloodless alternative to displaying strength through violence. While the classical revival did not bring peace to war-torn Europe, it was one of the most powerful cultural transformations in human history, and the export of humanism by explorers and missionaries made classical antiquity a vocabulary of power recognized from Mexico to Japan. In this sense, the Renaissance world was not limited to Europe, but included every part of the Earth that was touched by the revival of Greek and Roman antiquity.

The exhibit was made possible thanks to funding and support from a number of our on campus partner institutions, including the Smart Museum of Art, the Nicholson Center for British Studies, the Fishbein Center for the History of Science and Medicine, the Stefanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge, and the Lumen Christi Institute.